When developing applications for microcontrollers, it’s crucial to understand how your code and data are managed and stored in the device. Effective memory management ensures optimal performance and reliability, especially in resource-constrained environments typical of embedded systems. In this blog post, we will explore how various components of a microcontroller program are organized within the memory using a practical example that involves servo motor control and sensor interfacing.

#include <AFMotor.h>

#include <Wire.h>

#include <Adafruit_PWMServoDriver.h>

Adafruit_PWMServoDriver srituhobby = Adafruit_PWMServoDriver();

AF_DCMotor motor1(1);

AF_DCMotor motor2(4);

#define Echo A0

#define Trig A1

#define S1 A2

#define S2 A3

#define Speed 150

#define servo1 0

#define servo2 1

#define servo3 2

#define servo4 3

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(S1, INPUT);

pinMode(S2, INPUT);

pinMode(Trig, OUTPUT);

pinMode(Echo, INPUT);

srituhobby.begin();

srituhobby.setPWMFreq(60);

srituhobby.setPWM(servo1, 0, 340);

srituhobby.setPWM(servo2, 0, 560);

srituhobby.setPWM(servo3, 0, 140);

srituhobby.setPWM(servo4, 0, 490);

motor1.setSpeed(Speed);

motor2.setSpeed(Speed);

}

void loop() {

robotArm();

// delay(5000);

// int distance = obstacle();

// Serial.println(distance);

// if (distance <= 9) {

// motor1.run(RELEASE);

// motor2.run(RELEASE);

// motor1.run(BACKWARD);

// motor2.run(BACKWARD);

// delay(100);

// motor1.run(RELEASE);

// motor2.run(RELEASE);

// delay(100);

// robotArm();

// delay(100);

// motor1.run(FORWARD);

// motor2.run(FORWARD);

// delay(100);

// } else {

// linefollower();

// }

}

void linefollower() {

bool value1 = digitalRead(S1);

bool value2 = digitalRead(S2);

if (value1 == 0 && value2 == 0) {

motor1.run(FORWARD);

motor2.run(FORWARD);

} else if (value1 == 1 && value2 == 1) {

motor1.run(RELEASE);

motor2.run(RELEASE);

} else if (value1 == 1 && value2 == 0) {

motor1.run(BACKWARD);

motor2.run(FORWARD);

} else if (value1 == 0 && value2 == 1) {

motor1.run(FORWARD);

motor2.run(BACKWARD);

}

}

int obstacle() {

int cm = 0;

int distance = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

distance = 0;

digitalWrite(Trig, LOW);

delayMicroseconds(4);

digitalWrite(Trig, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(10);

digitalWrite(Trig, LOW);

long t = pulseIn(Echo, HIGH);

distance = t / 29 / 2;

cm = cm + distance;

}

cm = cm / 5;

return cm;

}

void robotArm() {

for (int S4value = 490; S4value > 290; S4value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo4, 0, S4value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S3value = 140; S3value <= 290; S3value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo3, 0, S3value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S2value = 150; S2value <= 190; S2value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo2, 0, S2value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S4value = 290; S4value <= 490; S4value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo4, 0, S4value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S3value = 290; S3value > 140; S3value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo3, 0, S3value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S2value = 190; S2value <= 320; S2value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo2, 0, S2value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S1value = 340; S1value >= 150; S1value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo1, 0, S1value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S3value = 140; S3value <= 290; S3value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo3, 0, S3value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S4value = 490; S4value > 290; S4value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo4, 0, S4value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S4value = 290; S4value <= 490; S4value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo4, 0, S4value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S3value = 250; S3value > 140; S3value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo3, 0, S3value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S2value = 320; S2value > 150; S2value--) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo2, 0, S2value);

delay(10);

}

for (int S1value = 150; S1value < 340; S1value++) {

srituhobby.setPWM(servo1, 0, S1value);

delay(10);

}

}Libraries and Object Instantiation

In any microcontroller code, such as those written for Arduino platforms, the inclusion of libraries is a common practice. For instance, consider the use of libraries like AFMotor.h for motor control, Wire.h for I2C communication, and Adafruit_PWMServoDriver.h for PWM servo driving:

Copy code#include <AFMotor.h>

#include <Wire.h>

#include <Adafruit_PWMServoDriver.h>

These libraries are compiled into the project, and their compiled code is stored in the microcontroller’s flash memory. They provide necessary functions and classes which your application can use to interact with hardware.

Instantiating Objects

Objects such as Adafruit_PWMServoDriver srituhobby; and motors defined with AF_DCMotor motor1(1); are stored in RAM. These objects maintain runtime state information, such as current motor speed or PWM settings, making RAM an ideal location due to its fast access speed and volatility.

Pin Definitions and Constants

The definition of pins and constants using preprocessor directives like #define Trig A1 or #define Speed 150 serves as a compile-time text replacement. These macros do not consume RAM or flash memory as they are replaced by their respective values directly in the code:

cCopy code#define Echo A0

#define Trig A1

Setup and Loop Functions

The setup() and loop() functions contain the core logic of a microcontroller program. The code within these functions, from initializing serial communication to setting up pin modes, is stored in the flash memory:

cCopy codevoid setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(Trig, OUTPUT);

// Additional setup code

}

void loop() {

// Main program execution loop

}

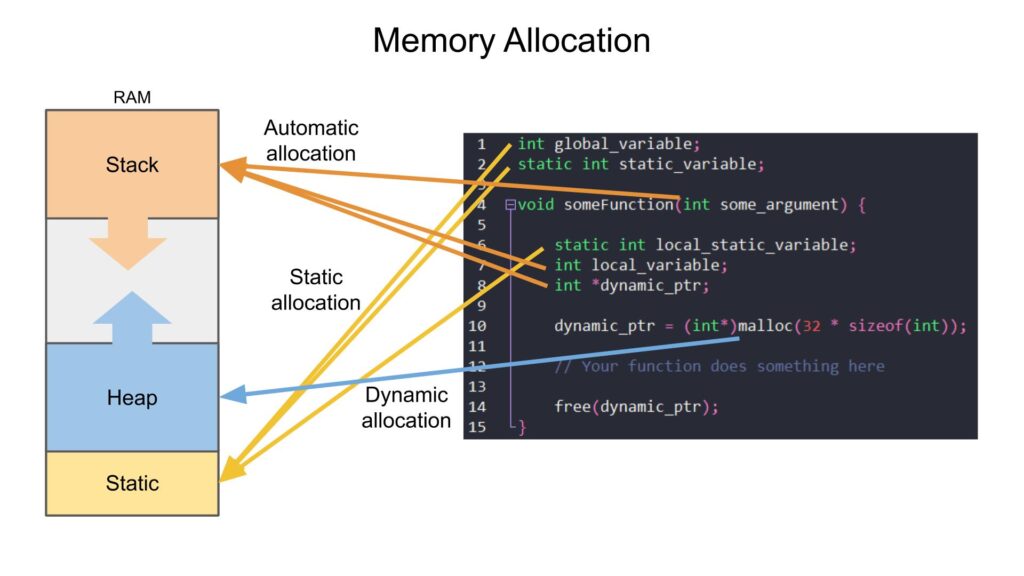

Function Execution and Stack Usage

Function calls and local variables, like those in a function designed to control a robot arm, use the stack which is part of RAM. This usage is temporary, just for the duration of the function execution, providing efficient memory management for runtime operations:

cCopy codevoid robotArm() {

// Control logic for moving servos

}

Interacting with Hardware

Functions such as digitalWrite() or digitalRead() interact directly with the microcontroller’s hardware, manipulating I/O registers. These registers are special memory locations used specifically for managing hardware resources and are not part of the standard RAM or flash memory:

cCopy codedigitalWrite(Trig, HIGH);

Conclusion

Understanding the segmentation of memory in a microcontroller helps developers optimize their applications for speed and efficiency. By allocating the right type of data to the appropriate memory segments—flash for program code, RAM for dynamic data, and registers for hardware control—developers can create robust and efficient embedded systems.

This overview not only sheds light on the behind-the-scenes operation of microcontroller programming but also helps in designing systems that are both reliable and effective at managing the constraints of device resources. Whether you’re controlling servo motors, reading sensor data, or communicating over networks, the principles of memory management remain a foundational skill in the world of embedded systems.

more details : https://www.digikey.in/en/maker/projects/introduction-to-rtos-solution-to-part-4-memory-management/6d4dfcaa1ff84f57a2098da8e6401d9c